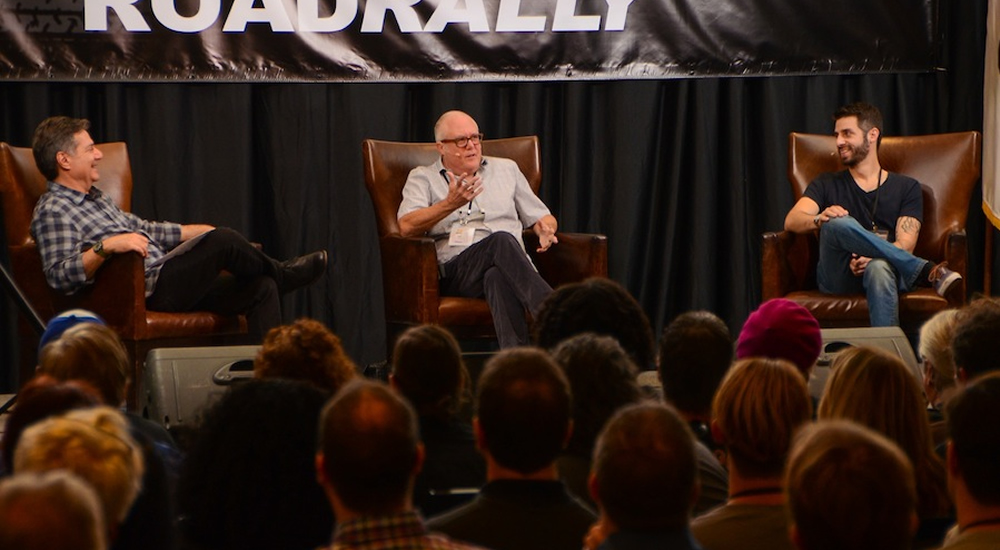

1,000 songwriters, artists, and composers listened carefully as Bob Mair (center) and Frank Palazzolo (right) shared critical music licensing information with TAXI’s Michael Laskow and the audience.

EDITOR’S NOTE: With the 2017 TAXI Road Rally just days away, we thought it might be a good idea to revisit some of the great music licensing advice given out at the beginning of the 2016 Rally.

Here are some snippets of timeless advice given out last year by Music Supervisor, Frank Palazzolo, and Music Library owner, Bob Mair. Give yourself a head start on this year’s TAXI convention by investing 10 minutes to read the pearls of wisdom doled out by these two music-licensing experts at the last year’s Road Rally!

I hear this all the time: “I’m published by ASCAP,” or “I’m published by BMI.” BMI and ASCAP are not publishers, and we’ll get into what they are. Bob, can you please define what a publisher is—because you are one?

Bob: Sure. A publisher is someone who represents writers, musicians, and artists. They sign an artist and some of their music—not necessarily all of the artist’s music, but some of their music. They represent that music to their clients—film, television, advertising, trailer houses, whoever they’re doing business with. In representing that music, they basically… It’s a pretty deep situation now, so we won’t get too far into it, but they register the songs with BMI, ASCAP, or SESAC on behalf of the writers, and then they represent that music to their client. So if someone’s looking for a Black Keys, or looking for something like Hans Zimmer—looking for something in a particular style—the publisher will send the music that they feel is appropriate to the client, and they negotiate the fees on behalf of the writers. Like I said, they make sure that the music is registered with the PROs so that the writers will get their performance income after the music is performed. They will also make sure the cue sheets are done appropriately, because cue sheets get screwed up. Humans are doing cue sheets. And then they also have to follow up with the PROs nine months later to make sure they’re actually paying the writers.

Let’s talk about cue sheets, Frank. Every piece of music that goes in a show lands on a cue sheet. Tell the audience what it is, who fills it out, what information might be on there.

Frank: Our music editor pretty much sticks in each cue [in the edited show], and each cue has its little cue number, and they have the in-and-out time, and the length of time that we’ve used it for, the type of use that it was [BV, BI, VV, or VI], and then those cue sheets get submitted to the PROs, the performing rights-societies or organizations. And then they calculate royalties. And how they do that is just a mystery to everybody. And then, after it goes through that whole thing, you get a check in the mail. And if the cue sheet isn’t submitted, you don’t get a check in the mail for that placement or use.

How often do cue sheets not get filled out, or not get filled out properly?

Frank: There are a lot of times, man, where people have come back to me and they’re like, “Hey, I just contacted ASCAP and they said they didn’t get a cue sheet for this thing. We worked on that six months ago.” And then I contact the music editor that I worked with, and they are like, “Oh, I thought you guys submit the cue sheets.” And then they contact the producer, and they’re like, “Didn’t you?” And I’m like, “The producer doesn’t do cue sheets!” And a lot of times it’s miscommunication, you know? Sometimes when people are new on the gig, it doesn’t mean that they don’t know how to do their job; it just means that they don’t know every single aspect of their job. So if a dude has only done two films, he might not get it. I had somebody contact me—record labels, trying to get their cue sheet information—and I’m just like, “What are you doin’, dude? You need to contact the publishers, not the record labels.” So you never know who’s handling it.

Bob: It’s part of the publisher’s job is to make sure that human error doesn’t cause things to fall through the cracks. [It happens] less with episodic TV, in my experience, from doing this a long time. It’s more in the reality-TV world, where things get a little funny, because a lot of times you’ve got interns doing the cue sheets. So you do have to stay on top of that stuff.

"Even if you’re gonna represent yourself, you need to learn the very, very basics of what you’re doing."-Frank Palazzolo, Music Supervisor

What percentage of your company’s time is spent tracking down that stuff to make sure that you and your writers get paid? Gimme a percentage.

Bob: Too much! It’s pretty much constant. Between tracking cue sheets… Every contract being signed, it says, “We get a cue sheet.” Just because it says it in the contract doesn’t mean it happens, so it’s a constant follow-up. NBC, CBS, ABC promo departments, making sure the promo departments are submitting their records that this quarter, the PROs, whatever. It’s constant!

My experience is that many of the writers and composers who are new to music licensing don’t understand what publishing is, and they don’t do a great job of keeping track of which songs or cues are published by whom. Any suggestions?

Bob: One of the things I would say is, when you write enough music, keep a spreadsheet with your titles; who you sent them to, who signed the track, and be very methodical with that. Don’t let that slide, because you want to know who is representing your music. Because three years down the way, you’ll be sitting watching television and all of a sudden you’ll hear a jingle, and “That’s my song!” Who’s representing it, and couldn’t they pick up the phone and call?

Frank: I know that we’re talking about publishing a lot. This is a 101 class. Songs are divided into a master recording, and in publishing there are two parts to your song. So what these guys are talking about is the writing portion of the song. I’m not talking about the artist’s recording part of the song. So when I ask you if you own the master, and do you own the publishing? And you say, “Yeah, I own it.” I need to know what you’re talking about. You own what? Do you own the recording, or do you own the master? “No, let me ask.” And did you write it by yourself? And they say, “No, I wrote it with a friend.” And I say, “Do they have a stake in this?” “Yeah, I think so.” That is the best way to show me that I can’t do business with you.

You’ve got to learn the business. So even if you’re gonna represent yourself, you need to learn the very, very basics of what you’re doing. So when I ask you a question like, “Do you own the master?” “Do you own the publishing?” And you answer, “100% master, 100% publishing,” or “100% master, 50% of the publishing, and the other person owns 50%, and no, they don’t have a publishing contract with anybody.” My response to that is, “Wow, this dude knows what he’s doing; this is a person I can do business with!”

Bob: So because I’m a publisher, I don’t know how you handle this. If somebody approaches you directly and there’s a 50/50 split and you’re talking to one of the two writers…

Frank: I need somebody to sign off on behalf of both of them. That’ll be the next level. So then we have something called a one-stop.

"If you’re going to represent yourself and there are multiple writers, whoever is doing the representation should have an administration agreement…"-Bob Mair, Publisher

How many of you guys in the audience know what one-stop means? I’m curious. [About 50% of the hands in the ballroom go up.] All right, I’m really glad you’re talking about this, because 100% of musicians pitching film and TV music should know this.

Frank: So what one-stop means is that if Bob calls me up and says, “This is a one-stop,” that means that he is able to license on behalf of the master and on behalf of the publishing even if there are multiple writers, even if there are multiple publishers, he can take care of it in one-stop. And if you know that term and you send me a song and you say, “This is one-stop,” that means that I know that you know what you’re doing. It’s pretty simple. If you just represent both sides of it and everybody involved in it, and you say you’ve got contracts where I can sign off on all of it, it helps your cause. Because if you have four writers on a song and it’s not the next Beyoncé track, I’m probably not going to take the time to send out four publishing request forms.

Bob: Yeah, if you’re going to represent yourself and there are multiple writers, whoever is doing the representation should have an administration agreement, something that says you can administer on behalf of all of us.

Nobody’s got that. How many of you guys have administration agreements with your co-writers? A very small percentage, maybe 5% of the people in this ballroom.

Frank: I’m surprised.

This is the reason we do TAXI TV and the Road Rally. Member Matt Vander Boegh is a great example. Five years ago he didn’t know all this stuff, and now he’s making enough money where he’s going to be able to walk away from his day job and do music full time. We really, really want our members to learn this stuff, because it’s not just about making cool music—there is so much more to it. A lot of musicians are very inclined to say, “I’m a creative person; I don’t want to do the business.” Well, a lot of the business will get done for you by giving up 100% of the publisher’s share to the publisher. They earn their money making sure that Frank doesn’t call me or call Bob or call somebody in the middle of the night and go, “Holy crap, I just got a phone call from CBS, and boy are they pissed off, because they just got a cease-and-desist letter from an attorney after somebody who was a writer on something and didn’t make it on to the cue sheet or the agreement. Now you’ve got a potential lawsuit. It probably won’t go that way, but…

Bob: Ah, no, it actually will.

It will? So let’s talk about that. Let’s put the fear of God into them, Bob.

Bob: Well, it’s a litigious world right now, and we are as a publisher, extremely careful. We dot our I’s and cross our T’s. I mean, even if a writer says it’s a one-stop to me, I get on the PRO sites and I see if that song exists anywhere else. And unfortunately, it has happened too many times.

So that’s before you’ll pitch it?

Bob: That’s before I’ll even sign it. Or I’ll search and see if the piece of music has been used in television before.

That’s a lot of work. I can’t even fathom the amount of time that a publisher must spend. And most of the publishers we’re talking about in the film-and-TV world are mom-and-pop shops, where it’s two people, three people, five people. There are some big ones obviously out there that are owned by Sony or Universal—big, giant libraries that might have 300,000 tracks and a staff of 50 or 100 people. But the vast majority of the music libraries are small, hard working companies.

Bob: Well, the smaller you are, the more detailed you can be. You know, it gets lost in the cracks. And, you know, truthfully—I’m a writer/producer myself—I’ve been doing this a while. I’ve worked with a lot of really great people—amazing writers—but when it comes to the business side, they are just not quite as about dotting I’s and crossing T’s. So it’s not that they’re evil people, but it’s just, “Oh, right, man, I did this like five years ago.” And you go, “Well, OK, so we can’t work with that song,” or “We can’t work with that piece of music.” It’s not like they are evil or they’re trying to take advantage of us, but things happen. Just like cue sheets not being filed, it’s just humans being humans.

"Just like the stock market or anything else, you wouldn’t put all of your eggs in one basket. You want to diversify your portfolio, and you want to be with the best publishers that are out there."-Bob Mair, Publisher

I want to talk about… Because both of you guys are artists or composers and do stuff yourself, would you sign a deal with a publisher that says, “I want 100% of the publisher’s share, and I’m not giving you anything upfront.” It’s an issue for our members, and my personal feeling is I would do a deal with Bob in a heartbeat if he wants 100% of my publishing and he’s not giving me anything upfront, because I know Bob. I know how hard Bob works, how effective he is, and how much money he makes for his writers. There are other people I wouldn’t do that deal with, so it’s a tough decision. So what can you tell them about how to judge whether or not to do a deal where they give up 100% of the publishing.

Bob: What I tell people that are really new to the situation… You know what? I turn a lot of people away that are so green, because in 26 years of doing this, the last thing I want to do is burn anybody. My business isn’t built on bad will. It’s built on good will. You know, the proof’s always in the pudding. You make somebody money, they keep coming back to you, and they bring you better and better music. But like you say, only time will tell with that.

As you know, there are some great publishers out there, I’m not the only one—in fact, we’re gonna be seeing some this afternoon [on the Music Library panel at the Road Rally] that do really clean business. But I tell people to tiptoe in.

Don’t put all your eggs in the first basket.

Bob: Exactly. These are assets. Your music is an asset; it’s a money-generating thing. So just like, dare I say, the stock market or anything else, you wouldn’t put all of your eggs in one basket. You want to diversify your portfolio, and you want to be with the best publishers that are out there. You have to do research. I have people approach me, and unfortunately, I hear some amazing music…just amazing. But I can’t sign it because I don’t have those clients. So rather than just absorb music and have it sit on the shelf, it doesn’t do me any good and it doesn’t do you [in the audience] any good. So I’ll just go, “You know what? We’re not the right place for you.”

I would do my research. Find out who’s doing what, who’s big in the advertising world, who’s big in the trailer world, who’s big in film and television, and just kind of find your… Because some of you guys are writing everything.

Frank, how about you? Taking off your music-supe hat for a minute and putting on your musician/writer’s hat. How do you feel about doing a publishing deal with somebody where you’re giving them 100% of the publisher’s share for no money upfront?

Frank: Well, my philosophy and what I’ve told people before, is how many songs have you written? So let’s just say I’ve written 50 songs. All right, you have 50 completed songs; how many songs have you made money off of? None of them! Yeah, you should sign a publishing deal. [laughter] You haven’t made any money, right? So sign a publishing deal. If somebody has a stake, if somebody is involved in the industry and they have access to music supervisors, if they know where the music’s gonna go and they want your music, that means they see a potential revenue in it. So obviously if they have your publishing, they’re gonna be trying to make it money. So I don’t see a major problem if you trust them and if you’re making no money. To give your entire catalog away in one shot, I agree, go little by little and see what happens. Just because you have a publishing deal with somebody, you don’t have to necessarily give them everything that you’ve got. Just ease in.

You’re always gonna write another piece of music.

Frank: Yes, you’re gonna write another piece of music. And also, if you just wrote it and you’re like, “This song is the best thing I’ve ever written,” don’t run out and go give that away. But if you wrote something 10 years ago and you still haven’t made money with it, hey, you’re due. It’s time to get somebody to make you some money, because obviously you haven’t figured out how to do it on your own. There’s no shame in that, but you need a little bit of work.