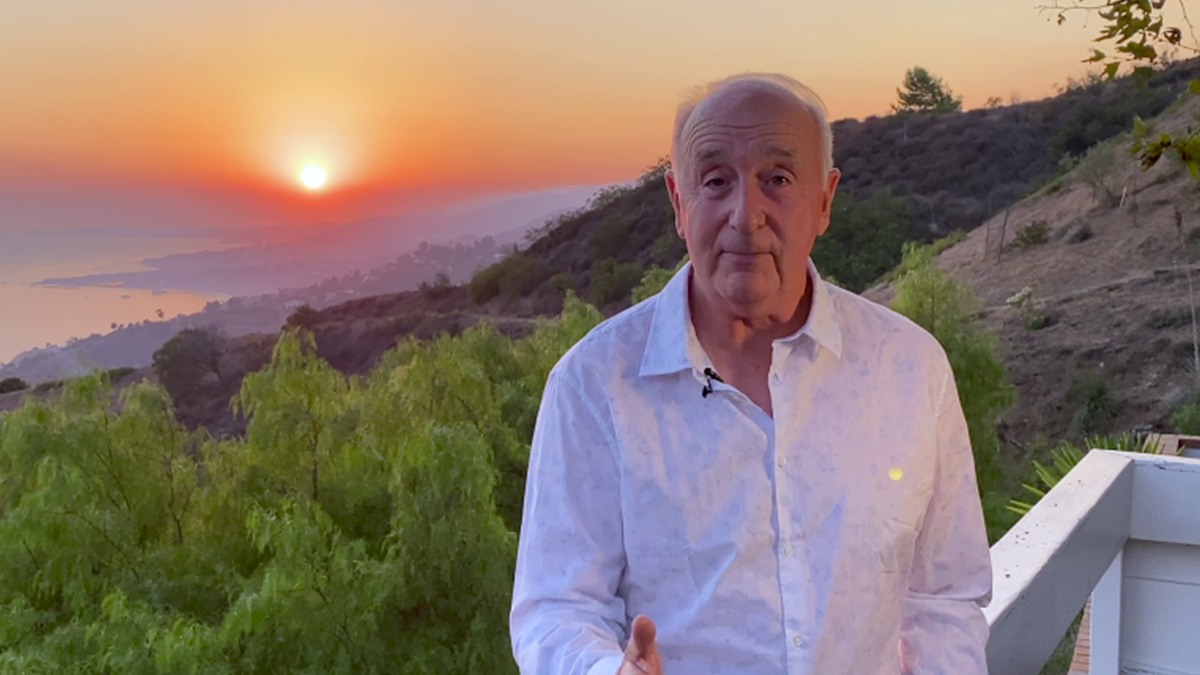

Interviewed by Michael Laskow

Years ago, one of our members took the phrase “Wash, Rinse and Repeat” and applied that to TAXI members sending their music to the industry through us. Members would just fret and sit by the phone waiting for it to ring and check their emails and texts every five minutes. Are they gonna sign this? Are they gonna put it in their catalog? And somebody came up with the phrase “Write, Submit, Forget, Repeat.” That has become a mantra for thousands of TAXI members—“Write, Submit, Forget, Repeat.”That applies to what you’re saying!

Yeah, I think that’s exactly right. Because what we’re really talking about here is a lifetime commitment, right? It’s not about one thing that is going to be a hit and is gonna change our lives. Actually, Seth Godin has a book coming out called The Practice, and what he talks about is having a practice—like you have a yoga practice, or you have a martial arts practice—that your art is a practice. And it’s absolutely the way I think about it. That it’s a lifelong commitment; I’m never gonna stop. It’s really about the process, that I’m gonna do one thing, and then I’m gonna do another, and then I’m gonna do another after that. And I’m gonna follow my muse, and I’m never gonna stop, and the fulfillment is in the daily practice. And if we have a hit, great! That pays the rent so we can keep doing it, you know? And if we don’t have a hit and it’s a bomb—and we all have plenty of bombs—then we should be way beyond that. By the time some project bombs, we should be on to project X and project Y and project Z, so we’re full of enthusiasm for the thing we are doing now, you know? I couldn’t agree more, it’s a practice.

Yeah, it is. Discipline. Discipline may be the sword that kills Resistance.

Yeah. And the other thing, Michael, is to be a musician is a dream, right? It’s like being an astronaut or playing center field for the New York Yankees. It’s not like being a roofing company or a driveway paving company or being a shirt salesman. Being a musician is an incredible thing, right? Think about that, that you could be living with a keyboard, coming up with art and beautiful stuff, what an incredible thing. So, part and parcel of that a lot of times is we have this belief that we are gonna produce something and it’s gonna be the White Album, and as soon as it hits the stores our life it gonna change, right? Women are gonna come pouring through the windows, money is gonna flood, and we’re gonna change. Our DNA is gonna change, right? Which, of course, it is completely false. I mean, sometimes it works out for Guns N’ Roses and guys like that, but next thing they wind up in rehab or committing suicide.

So, the idea of a practice is the antithesis of that. It’s not that we’re hoping that some hit is gonna save us and our life is gonna change. It’s not gonna change. What we have to do is our work every day—sitting down at that keyboard, whatever it is—and that’s where the satisfaction comes from…at least for me. I know I’m probably preaching to a lot of people who think this is a bunch of crap—“I’ve got to make a living.” But it never hurts to love what you do. It’s a practice; it’s a lifelong commitment.

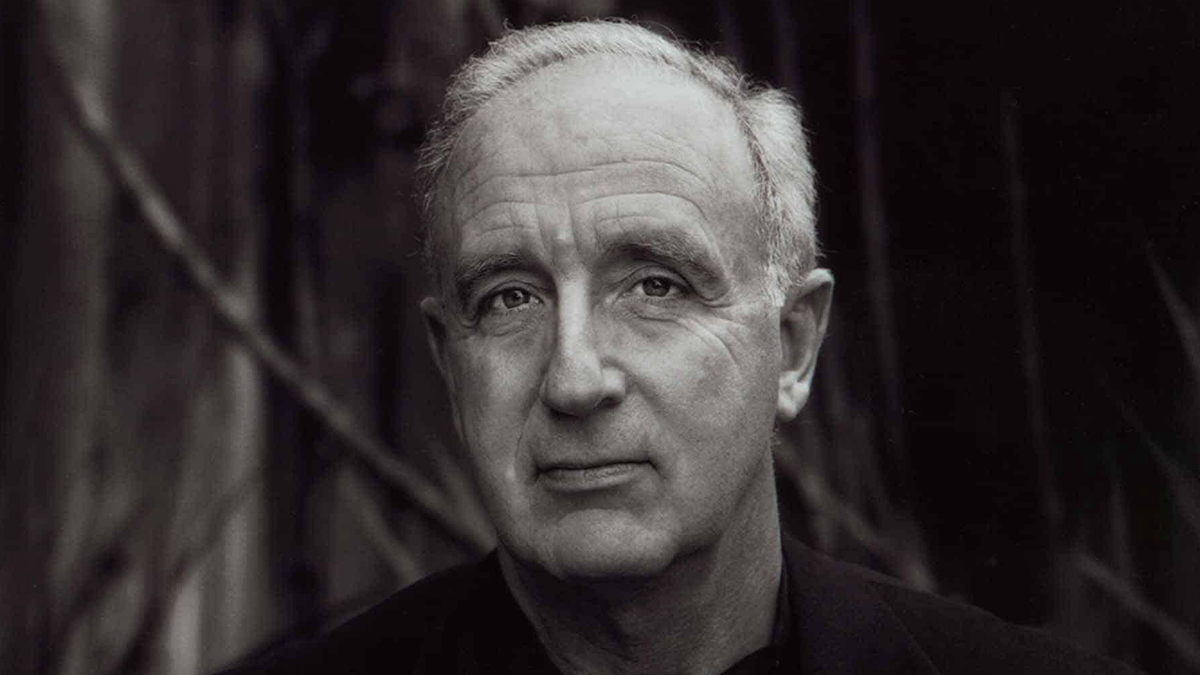

I’m just sitting here amazed listening to you. Literally, I feel like I don’t have to ask another question, because everything coming out of your mouth is incredibly valuable. And I’m listening to this and asking myself, “How could this guy ever wake up in the morning and have Resistance?” How could you, Steve Pressfield, have Resistance?

Well, it’s a great question, Michael. Of course, I have enormous Resistance. And right now, I’m just starting to write a new book. And the form the Resistance is taking is a voice in my head saying, “Who’s gonna give a damn about these stupid stories of your life?” It’s a completely convincing voice that I’m fighting every day. So, I have enormous Resistance, and Resistance never goes away.

And let me say one other thing that might be of help to our viewers here. It’s a law of Resistance that the more important a project is to our evolution as a soul—as an artist—the more Resistance we will feel to it. If it’s just some little insignificant project that we don’t really care about, we won’t feel any Resistance at all. But if it’s, you know, the Ninth Symphony, we are gonna feel monumental Resistance to it. So, the bottom line of that is, if anybody who is listening to this is experiencing huge Resistance to some project they are working on—and I should listen to this myself too—if you are feeling massive Resistance, it shows that whatever it is you are working is really important to you. So, press on in the teeth of it, even if you have to be like [TAXI member] Randon Purcell and get up at four in the morning and go down to the basement. Do the work and press on. And I’m listening to that myself as I’m saying it, and I’m encouraging myself to keep working.

“I don’t think we’re entitled to anything, but I do think we are born with a destiny.”

Somewhere in one of your books, you talk about people coming into the world with a specific personal destiny; that they’re not a blank slate. You know, we all tend to think that a baby comes out… I said this to a friend of mine recently who had a new baby, I said, “Aw, look at that, a little blank slate.” You think otherwise, and I agree with you. Most people in this virtual ballroom that we’re in today probably feel like they were put on this Earth to become a successful musician. Is there a difference between fulfilling that destiny, or feeling entitled to it? Entitlement is a bitch, I think.

Um... Yeah. First of all, I don’t think we’re entitled to anything, but I do think we are born with a destiny. You know, they call it the Daimon, which the Greeks thought was kind of an adhering spirit that was with us and that kind of knew our destiny and carried our destiny. But then, that Daimon, we have to do it. It is on us to do it, and it’s on us to do it in the face of massive Resistance. One of the things Resistance will do if we have a destiny, it will try to talk us out of that destiny, try to push us away from that destiny.

So, we have to pay our dues. Learn the craft, put in the time and, more important, self-belief. Somehow acquire that self-belief. Connect to the muse, connect to the source of inspiration and trust it. And entitlement has nothing to do with that at all. If anything, Resistance is exactly the opposite of entitlement. It is what tries to undo every hope that we were born with, I am certainly a believer that we come into this world… And if you look at children… If you have three kids, each one is completely different. They are their own self, right from the beginning, right? And you can’t change them, and it’s the same with all of us.

I quote in The War of Art a poem from Wordsworth, “Intimations of Immortality,” where he says that “Not in utter nakedness do we come”—meaning our souls into this life—“But trailing clouds of glory do we come from God, who is our home.” So, he certainly believed that we all are born with a destiny. I am a believer that we are born with a body at work. If you think of the albums that Bruce Springsteen has done, I believe when he was 11 years old those albums existed in some plane or potentiality, whatever you want to call it. They were an alternative future. And what he did was, he brought them into material form, and God bless him for doing it. And that’s us as artists. That’s our job, to believe in that body of work and then bring it forth.

How can one teach oneself to not take rejection personally? In one of the books, I think you said that evolution has programmed it, or baked it into our gut. How do you shake that off and not take it personally, because the thing that you are being rejected about came out of you? How do you beat it?

It’s really hard, there’s no doubt about it. We all hate to be rejected. I heard a story about Cole Porter one time. And Cole Porter used to—at least at one time in his career—he worked in Hollywood doing songs for musicals or movies. Somebody said to him one time… He did some wonderful song that went on to become a great hit on the radio but was rejected by MGM, or whatever it was. And somebody said to him, “Mr. Porter, how do you deal with this rejection? How do you handle this? They just shot down this wonderful song that you wrote.” And he said, “I got a million of ’em. Send me back to the piano, I got a million of ’em. There’s another trolley coming down the track.” And I think there’s a lot to be said for that. And the other way of looking at it is, “Screw ’em.”

What we are doing is a practice, it’s a lifelong thing, and we’re gonna keep going no matter what. But it’s very hard. If you can do that, if you can somehow get by rejection, boy, is that a strength.

You know what, you guys in the chat room, we’re gonna have an extra 10 minutes so I can have you guys ask Steve some questions. So get them ready and post them in the chat.

“One of the many diabolical forms that Resistance will take is like when a painting is done, it will tell you to keep working on it, keep noodling with it. It’s trying to ruin us. It’s also a skill as an artist to know when to stop.”

Somebody asked what an arc in a song or an instrumental cue was about two weeks ago. And you have stated that in any project or enterprise, it can be broken down into a beginning, a middle and an end. And then you fill in the gaps, and then fill in the gaps between the gaps. How do you know when you have filled too many gaps? You’ve put too much icing on the cake.

Well, that’s another great question, Michael. And I guess it sort of comes down to instinct in a sense. I once asked an agent of mine if a book of mine was too long, and he said, “How long is a letter? Some letters are short, some letters are long. It all depends on what the project is.”

But I will say this about Resistance. One of the many diabolical forms that Resistance will take is like when a painting is done, it will tell you to keep working on it, keep noodling with it. It’s trying to ruin us. It’s also a skill as an artist to know when to stop. When is enough, enough? I also had this same agent—my first agent—tell me another thing once when I was finishing a manuscript and he wanted to get his hands on it, to take it out. And he said, “Where do you stand? How near are you to the end?” And I said, “It’s close. It’s close.” And he said, “Close is good enough, give it to me.”

That’s not always right, because sometimes you really want everything to be absolutely perfect. But what he was saying was, “Don’t noodle with this thing. Don’t noodle it to death. And it’s good enough, get it out there, show it to somebody.”

Oh yeah. Perfectionism is the death of a lot of things.

A form of Resistance.

Here’s a question from the chat room: “Was it as simple as submitting your early books to a publisher, or did it even then have to do with contacts you made along the way to get somebody to respond?”

When I started, when I broke through in the mid-’90s, it was a whole other world. It was pre-internet, pre-Amazon, pre-all that sort of stuff. So, it was old-school publishing where you had to have an agent and the agent would take it to a publisher, and that kind of thing. A much simpler world; I wish we could bring it back. But I never had any networks or anything, the only thing I ever had was just an agent. I never knew anybody, and I don’t even want to know writers because it’s too depressing.

The last studio I worked in—back in the day—had a giant, beautiful SSL state-of-the-art recording console, digital tape machines, everything you could want. Now I’ve got way more than that technology on my laptop with Logic Pro X on it. One of the problems I see—part of Resistance, I’m sure—is the technology. Even though it provides you the smorgasbord of possibilities is that you have a smorgasbord of possibilities. I’ve got 1,200 different bass drum sounds; I’ve got 78 different hi-hat sounds; I’ve got 252 electric guitar sounds. And you can sit there and just audition, audition, audition, and pretty soon the auditioning of the sounds and the moving around of parts and all the editing that you can do with that technology provides you with becomes Resistance. It prevents you from just shipping, as Steve Jobs would say.

It’s true. It really is true. I never even thought about that, because, obviously, as a writer you just have a keyboard. But I’m sure that it’s exactly true what you’re saying. If fear of success is the real killer here, when you have something like all those resources, it’s like they have taken away all the excuses for why you can’t succeed, right? For all of us, “You should be able to succeed right now” is common. The Beatles didn’t even have this. And, of course, that’s not true, because you have still got to write it. You’ve still got to get through your own Resistance and write the damn thing.

“You can’t just come up with just anything, it’s gotta be great. And to do something great, it takes a long process.”

You just brought up an interesting point, which I actually made a note about late last night, which was that we live in a fast-food world, you know, immediate gratification everywhere we look, largely because of Google, tech in general, and the internet. So any answer you want, it’s out there in an instant; anybody you want to communicate with, out there in an instant. We can expect the first or second song to be great because of that. We’ve been trained to think that everything comes that easily, so we’re been taught that our first or second song is gonna be a hit. How can we learn to understand the value of delayed gratification?

Well, you’re right, that’s today’s world. I mean, for me, obviously, my whole life was delayed gratification. So I couldn’t break through no matter what I did, and I think that that is reality. We made this fantasy about an iPhone or about, you know, instantly you do a sex tape, and you are instantly an Internet star. It’s a fantasy, it’s a fantasy—not true. Just because it happens to Kim Kardashian doesn’t mean it’s gonna happen to the 18 million other girls that did the exact same thing.

In reality, it’s hard. If you want to have an easy life, be a brain surgeon. Just go to school for eight years. If you want to be in this business, you’ve got to pay heavy dues, unless you’re lucky, unless you’re Bob Dylan or Neil Young or somebody. That’s just the way it is, you know? Because we are trying to create something—music or a book—that people, of their own free will, are gonna pay money for. And how hard is that? You can’t just come up with just anything, it’s gotta be great. And to do something great, it takes a long process. It takes a long time. If I had a young person, I would somehow beat that into their brains. It’s not easy.

Well, I was going to ask you for a closing thought, but I think you just gave it to me. Steve, this interview has been more than I could have possibly hoped for. Thank you so much for saying yes, for sharing what’s in that big brain of yours that remembers everything, and sharing it with our audience, and being the launching pad for this whole weekend. You were great, Steve!

Thanks for having me, Michael. I wish you guys all the best for this event. I’m sure it’s gonna be great all the way through. My best to everybody that’s listening in, and God bless you. And Randon Purcell, down in the basement at four in the morning, God bless you. You’re doing the Lord’s work.

Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Steven Pressfield!

If you’d like to purchase Steve’s life-changing book, “The War of Art,” that thousands of TAXI members have read. You can find it in all of its forms, here.