So, you want to know how the music industry works? You want a high-level overview of the music business? Maybe even some pretty diagrams that explain how it all works? Well hold on tight! Take a deep breath, and follow me down the rabbit hole.

Special Notes:

- For everyone’s sanity, I’ve limited the scope of this article to recorded music. Live music and performances introduce a lot of other complications, and so that’s best left for another article.

- This stuff is crazy complicated; I’m still learning and I make mistakes. If you see something, say something, so that everyone can benefit, including me.

- Please realize that I’m writing from the perspective of a US-based musician. Much of this still applies to you if you live outside the US, but you’ll want to double-check just to make sure.

Too anxious to follow me step by step? Then fall down the hole (i.e. scroll down) all the way to the end of this article where you can find the insane, huge diagram that explains it all (sort of). Don’t say I didn’t warn you! For the rest of us, let’s descend the abyss together, one step at a time.

First things first!

I’m not sure why, but it took me decades before I realized that a song has two distinct parts, each with its own copyright. Not one copyright, but two. One copyright for the composition and one copyright for the sound recording of that composition.

OK, then... what is a composition?

When a writer composes a musical melody with or without lyrics, a musical composition has been created. Compositions are also referred to as musical “works.”

As soon as that composition is written down or recorded, that composition is automagically copyrighted (at least in the US). You don’t actually need to submit a form to the US Copyright Office to get your basic copyright protection. If you do submit to the US Copyright Office, you’ll get some other benefits... but it isn’t necessary in order to be granted your basic rights. The composition copyright code in the US Copyright Office usually starts with “PA” (performing arts).

What is a sound recording?

Every time someone creates a new finished recording of a performance of a composition, a new sound recording is born. Sound recordings are also often called “master” recordings because they refer to the final master mix of all of the tracks and stems that make up the recording; to put it another way, masters are what artists finally burn to CDs or upload to iTunes to sell.

Similar to the composition, as soon as a sound recording is created, it is automagically copyrighted (in the US). You can go through the official process with the US Copyright Office, but that is not needed to get your basic rights. The sound recording copyright code in the US Copyright Office usually starts with “SR” (sound recording). Note that it’s possible to formally copyright both the composition and sound recording with the US Copyright Office on one SR form... so you should look into the details of a specific copyright before assuming someone didn’t file for the composition copyright, too.

It’s important to note that one composition can have many corresponding sound recordings. For example, Leonard Cohen wrote and recorded the song “Hallelujah,” but who knows how many artists, such as Jeff Buckley, created their own cover versions of that song! All of those artists’ sound recordings came from the same single composition by Leonard Cohen.

Remember that there is a lot of symmetry.

It’s really helpful to remember that the music business is quite symmetric. What I mean by that is there is often a corresponding company, organization, service, or feature on the other side. If something exists for the composition, a similar thing probably exists for the sound recording, and vice versa. This general rule can help you make sense of what you need to do and who you need to work with.

There are two components to a song.

Therefore, it’s absolutely vital that you first understand there are two distinct components to a song that control most of the music industry. Much of the music world is divided into stuff having to do with either the composition or the sound recording. Many music businesses and services are in some way tied to one or both of those. More importantly, almost all royalties can also be divided between the two.

In other words, 99% of the time (I just made up that statistic) you can determine in which bucket a company, organization, service, or feature operates by asking yourself this question: “Does it have to do with the composition or with the sound recording?” It’s like a binary search. As soon as you figure out if you’re dealing with the composition or the sound recording, you’re able to throw away half of the confusing information and narrow in on the other half of the confusing information that actually matters. Of course, some things deal with both... but that’s also good to know, and you can usually track down what happens to each side separately.

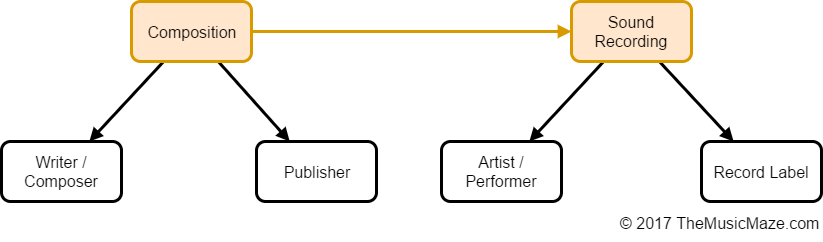

There are four primary stakeholders for a song.

It gets even better because both the composition and the sound recording can each be divided in half into two groups of people that have some skin in the game (aka stakeholders).

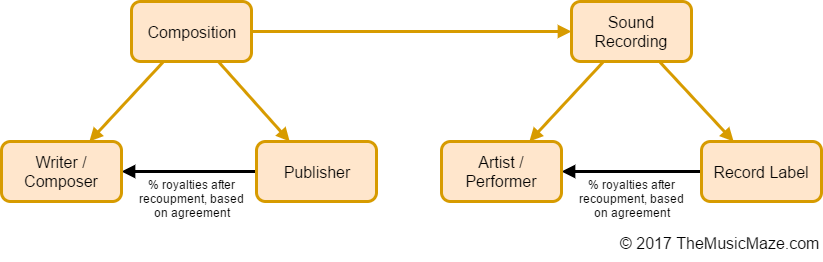

There are two primary stakeholders for the composition: the writer (composer) and the publisher. If you are a solo independent songwriter, you are both the writer and the publisher. You’ll see below that the writer gets royalties as well as the publisher. The publisher usually is the one that owns the composition copyright.

Likewise, there are two primary stakeholders for the sound recording: the artist (performer) and the record label. If you are a solo independent performer, that means you are both the artist and the record label. The record label usually is the one that owns the sound recording copyright.

That’s a perfect example of the symmetry I was talking about above. Two on one side, two on the other. The publisher owns the composition copyright, while the record label owns the sound recording copyright. Beautiful.

That gives us four primary stakeholders:

- Writer

- Publisher

- Artist

- Record Label

Each of those stakeholders can be further divided, as in the case when there are multiple writers, publishers, artists, or record labels involved. Or when a producer or mixer takes a portion of the writer’s or publisher’s share. You get the idea. But at this point, let’s just leave it at four main entities to keep things simple.

Oh, and for those who have separate publishers or record labels, your deal probably specifies what portion of royalties they collect should be shared with you, after they recoup any costs and money that you owe them.

Got to keep them separated!

If you’re a solo independent singer-songwriter, you usually write and record your own songs, which means you own both the composition and the sound recording. You’re the writer, publisher, artist, and record label all rolled into one. No wonder everything just sort of blurs together, right? Even in this case, however, you should think of yourself as four separate entities, since you are often treated as such in the real world anyway.

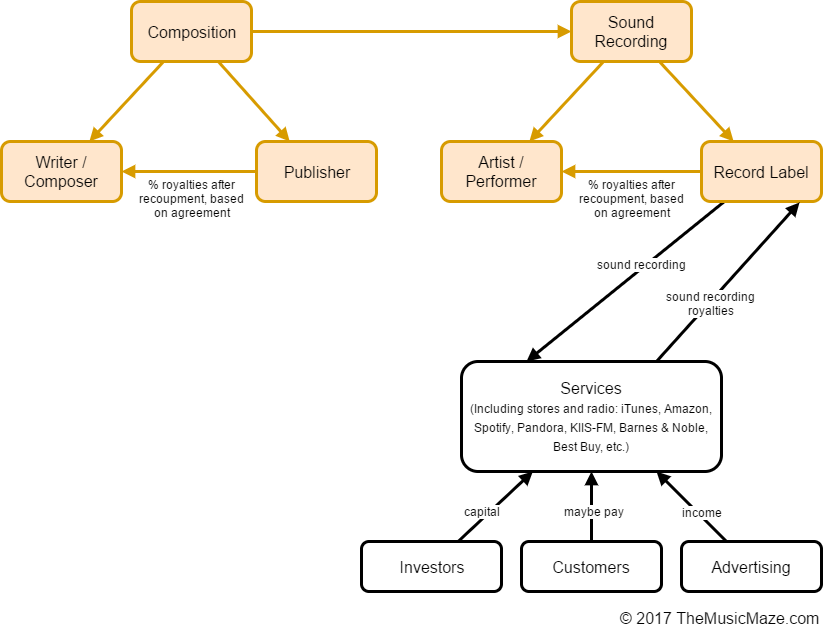

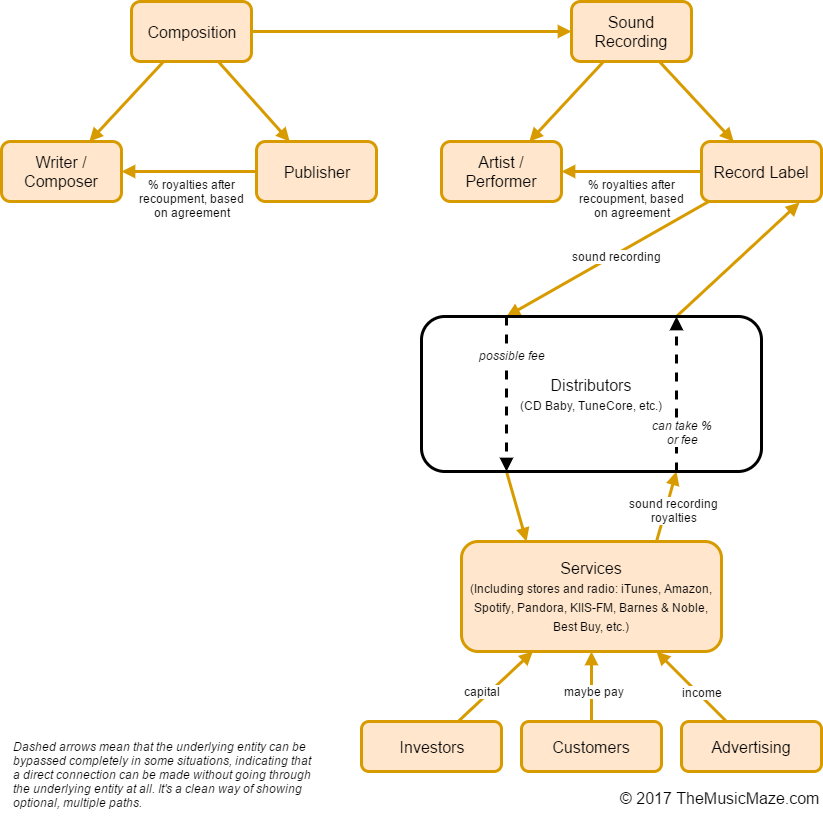

Start by putting your sound recordings on music services and in stores.

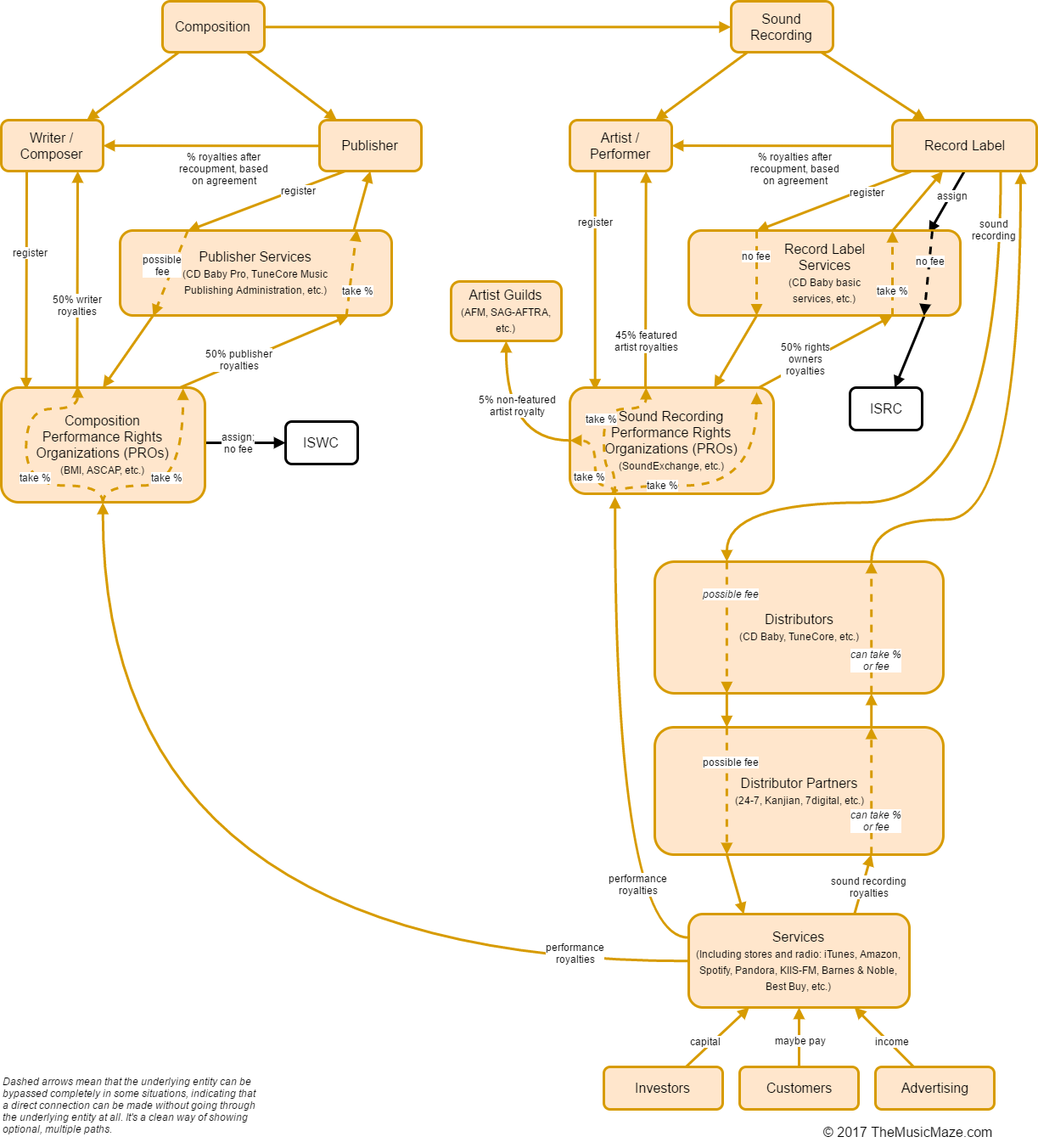

In order to get your music heard, you want to set up your sound recordings on all the various music services, such as iTunes, Spotify, Amazon, and put your CDs in stores like Barnes & Noble, Target, etc. Here’s what the diagram looks like with those music services.

Just a reminder: we’re just talking about services as they apply to recorded music (i.e. these diagrams won’t include details about live performances).

Here come distributors and aggregators to help us!

It would be super hard to sign agreements with, send your sound recording information to, and collect royalties from each service individually. That’s where distributors (or “aggregators”) like CD Baby, DistroKid, Tunecore, Ditto Music, and RouteNote come in. A distributor will work with all of those services directly without you having to, in exchange for a fee and/or percent of the royalties you get. You just have to do the work once with the distributor, and they do the rest. OK, seems fair. Let’s add them to the diagram.

NOTE: With this flowchart, you’ll start to notice that I’m including dashed arrows in the diagrams. Dashed arrows mean that the underlying entity can be bypassed completely in some situations, indicating that a direct connection can be made without going through the underlying entity at all. It’s basically just a clean way of showing optional, multiple paths without having to draw them all and clutter up the screen. For example, in the picture above, those dashed lines mean that a record label can work with a service directly and get paid from a service directly, OR a record label may choose to work with a distributor as a middle man. In other words, as these charts get more complex, you’ll want to remember that just because a line goes through an entity using dashes, it doesn’t mean that entity has to be used at all in practice.

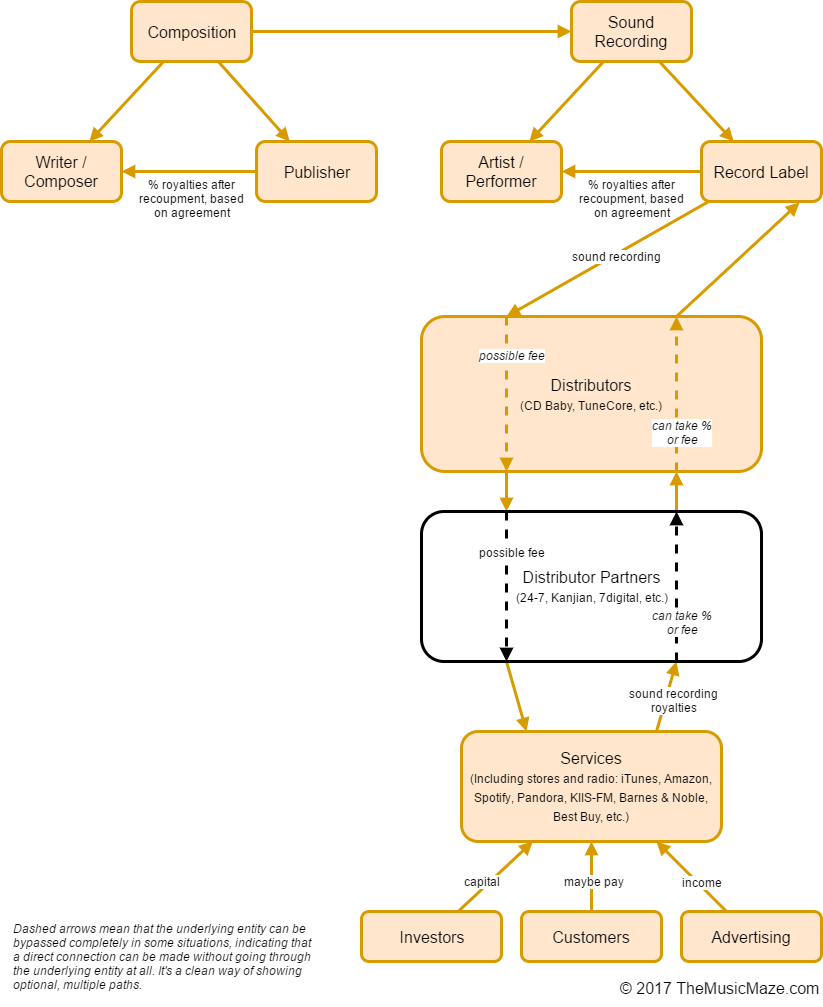

Even distributors need partners to help them out.

That’s right, things are so complex that even distributors can’t tackle it all. For example, a distributor in the US probably knows very little about how to get your music into all of the services that are in say Africa. Rather than throw their hands up and skip Africa, they partner with another distributor or company that knows how to work with the services in Africa, in exchange for... (say it with me) a fee and/or percent of the earnings.

OK, let’s add those distributor partners to the diagram and see what we get.

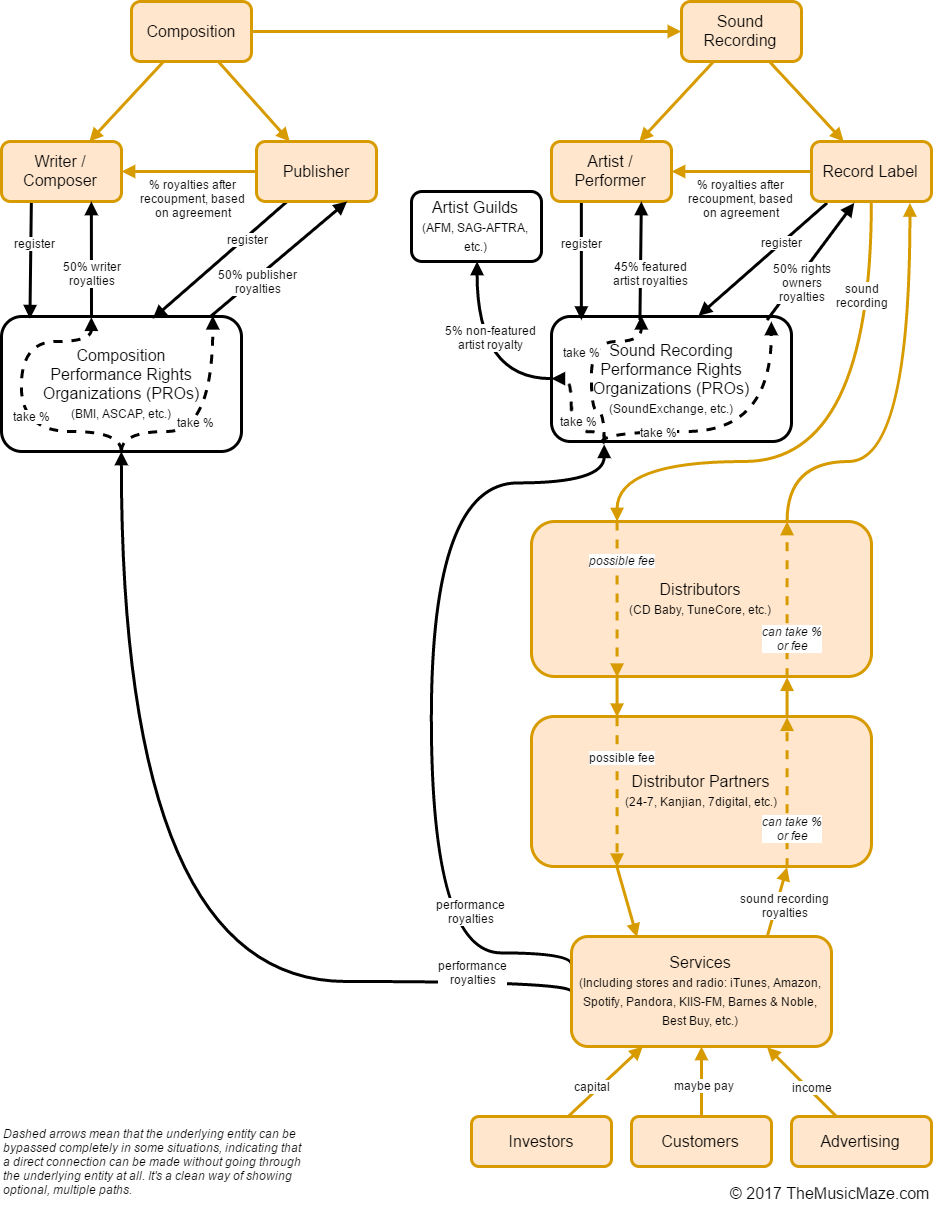

Here come performance rights organizations to collect performance royalties.

A Performance Rights Organization (PRO) exists to collect your royalties due to you when your composition and sound recording are performed. For the composition, the main PROs in the US are BMI and ASCAP. For the sound recording, the main PRO in the US is SoundExchange. I have other articles that go into boring detail about PROsand which ones to sign up with, and how to sign up with them. If your brain hasn’t exploded already or by the end of the article, you can go check out those articles... but stay with me for now because we’re on a roll and really starting to pick up steam!

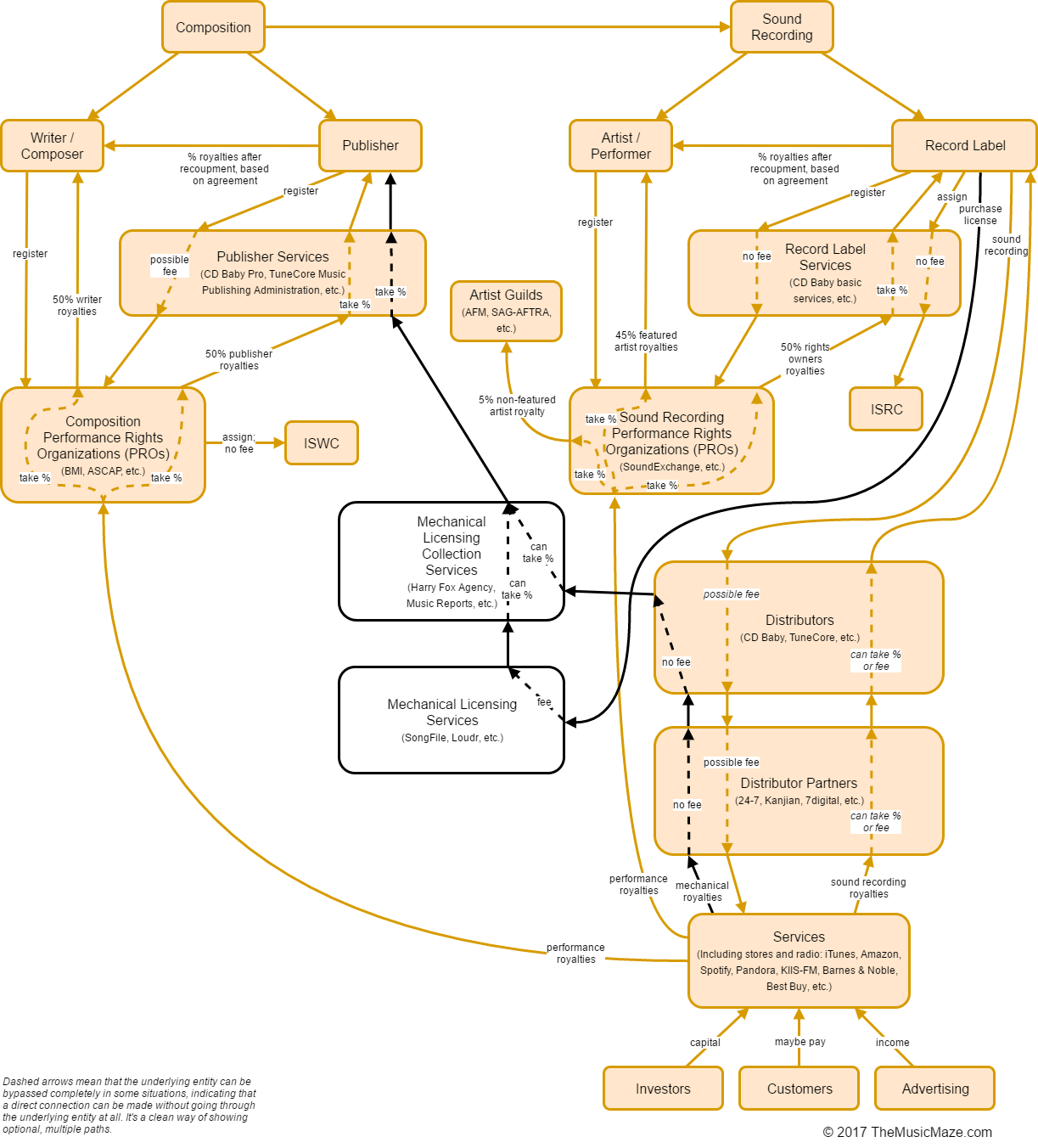

Here come special administration services to help out publishers and record labels.

Do you see the pattern yet? When we put in one type of company, we add another type of company that helps out that company. The same goes with performance royalties.

On the composition side, we’ve got services like CD Baby Pro and TuneCore Music Publishing Administration. These are often add-on services of other companies, such as CD Baby and TuneCore. They’ll register a publisher’s compositions with the PRO (BMI, ASCAP, etc.) on behalf of the publisher, act as the publishing administrator, and give the publisher back the publishing performance royalties directly, in exchange for a percent of everything they find. They will also sign up with the mechanical license collection services around the world that have been collecting the publisher’s mechanical royalties, and then give those back to the publisher, in exchange for a percent of everything they process.

On the sound recording side, we’ve got companies like the distributors themselves. For example, CD Baby offers to automatically register the sound recordings with the PRO (e.g. SoundExchange, in the US) on behalf of the record label, in exchange for a percent of the royalties that would normally go directly to the record label. They’ll also often offer to “create” and assign ISRC codes to the record label’s sound recordings, in case the record label didn’t assign them already.

Just a second... what is an ISRC code?

To help keep track of compositions and sound recordings, the world has devised two types of codes: the International Standard Musical Work Code (“ISWC”) and International Standard Recording Code (“ISRC”).

An ISWC uniquely identifies a composition, while an ISRC uniquely identifies a sound recording. That means, of course, that you can’t reuse codes for new compositions or sound recordings. Every new composition needs a new ISWC, and every new sound recording needs a new ISRC. The ISRC code in particular is used by all sorts of companies and services so that they can match up sound recordings with each other.

On the composition side, your PRO (such as BMI or ASCAP) will generate an ISWC for each new work you register. Go take a look at your existing registered work catalog with them and you’ll probably find the code somewhere.

On the sound recording side, the ISRC is usually assigned by the record label. If you don’t have ISRC codes, your distributor will likely offer you some. The ISRC code has a prefix that identifies the country and company who owns the ISRC code. You can get your own ISRC prefix for free and assign your own codes.

Here’s what the diagram looks like with the ISWC and ISRC codes.

What about mechanical royalties?

Ah, yes, mechanical licenses and royalties! You can read all about them in my other articles. In short, a mechanical license is needed whenever you want to publish a sound recording you make of a composition you don’t own (i.e. you record a “cover song”). Every time that sound recording is “used,” it requires a mechanical royalty to be paid to the publisher of the composition. See my other page for what I mean by “used.”

There are companies that help you obtain the proper mechanical licenses and pay the publishers. There are also companies out there that help manage the collection and reporting of those royalties from all around the world.

Here’s where we stand now.

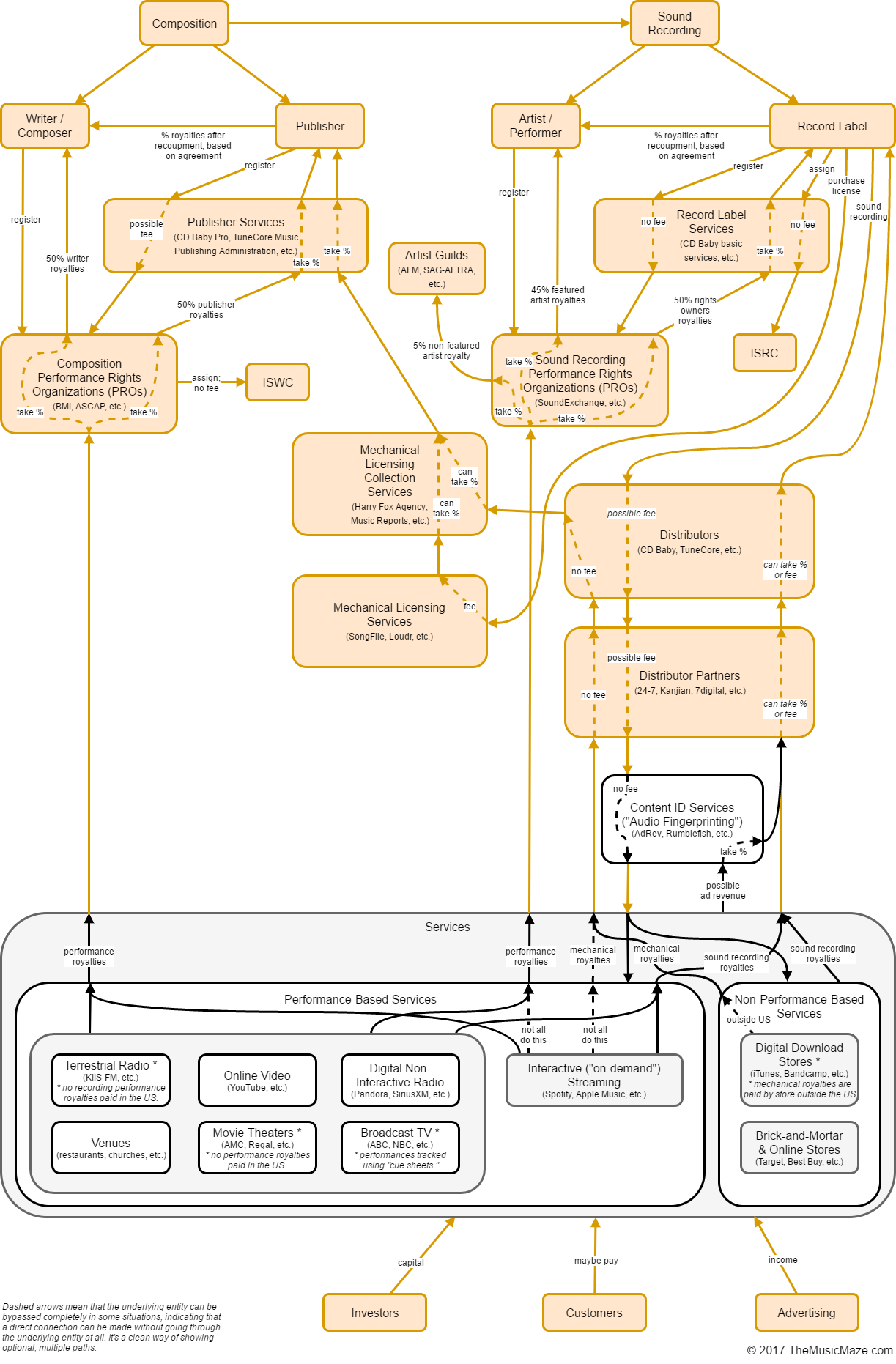

Can we go into more detail with how the services work?

Sure thing, but let me warn you that I know where this is leading, and this isn’t going to end well! We just opened up a whole new can of worms! There are a ton of music performance types for recordings, each generating different types of royalties with different rules, regulations, and companies that help them along.

Services and platforms come in all shapes and sizes, and they all can generate different types of royalties with different calculations. I’ve broken the services down into two main types to make it easier to follow: performance-based and non-performance-based. Again, please remember that this article is just talking about recorded music. Live performances (i.e. people playing instruments or singing in real life) are not included.

Performance-based services include things like the following:

- Terrestrial radio, such as KIIS-FM.

- Digital radio (i.e. non-interactive streaming), such as Pandora (the original version), iHeartRadio, and SiriusXM.

- On-demand (i.e. interactive streaming), such as Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon Music Unlimited.

- Broadcast television, such as music used in a TV series or commercial on ABC or NBC.

- Movie theaters, such as music played during a movie at AMC or Regal.

- Online videos, such as music used in a YouTube cat video.

- Venues, such as music piped into restaurants or in a church.

Non-performance-based services include things like the following:

- Digital download stores, such as iTunes and Bandcamp.

- Brick-and-mortar and online stores selling physical CDs, such as Amazon, Target, Best Buy, and Barnes & Noble.

An easy way to think of those two groups is like this: if it is a performance-based service, then performance royalties will be generated and paid to PROs; otherwise, it is a non-performance-based service. For example, Spotify is a performance-based service, which means you’ll also get money from the PROs for plays on Spotify. And similarly, a CD sold at Best Buy will not give you money from the PROs.

Here’s what the flowchart looks like now.

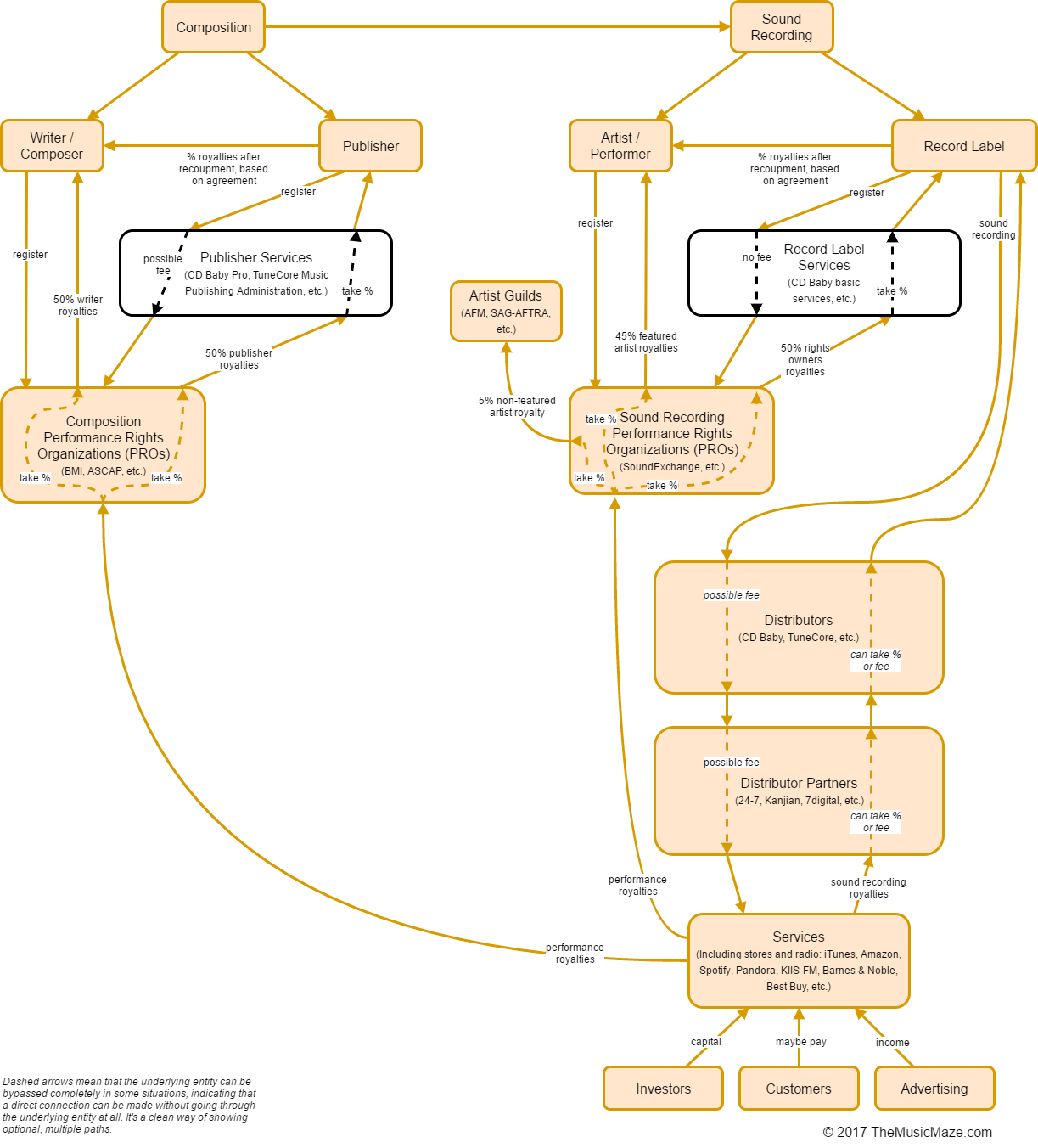

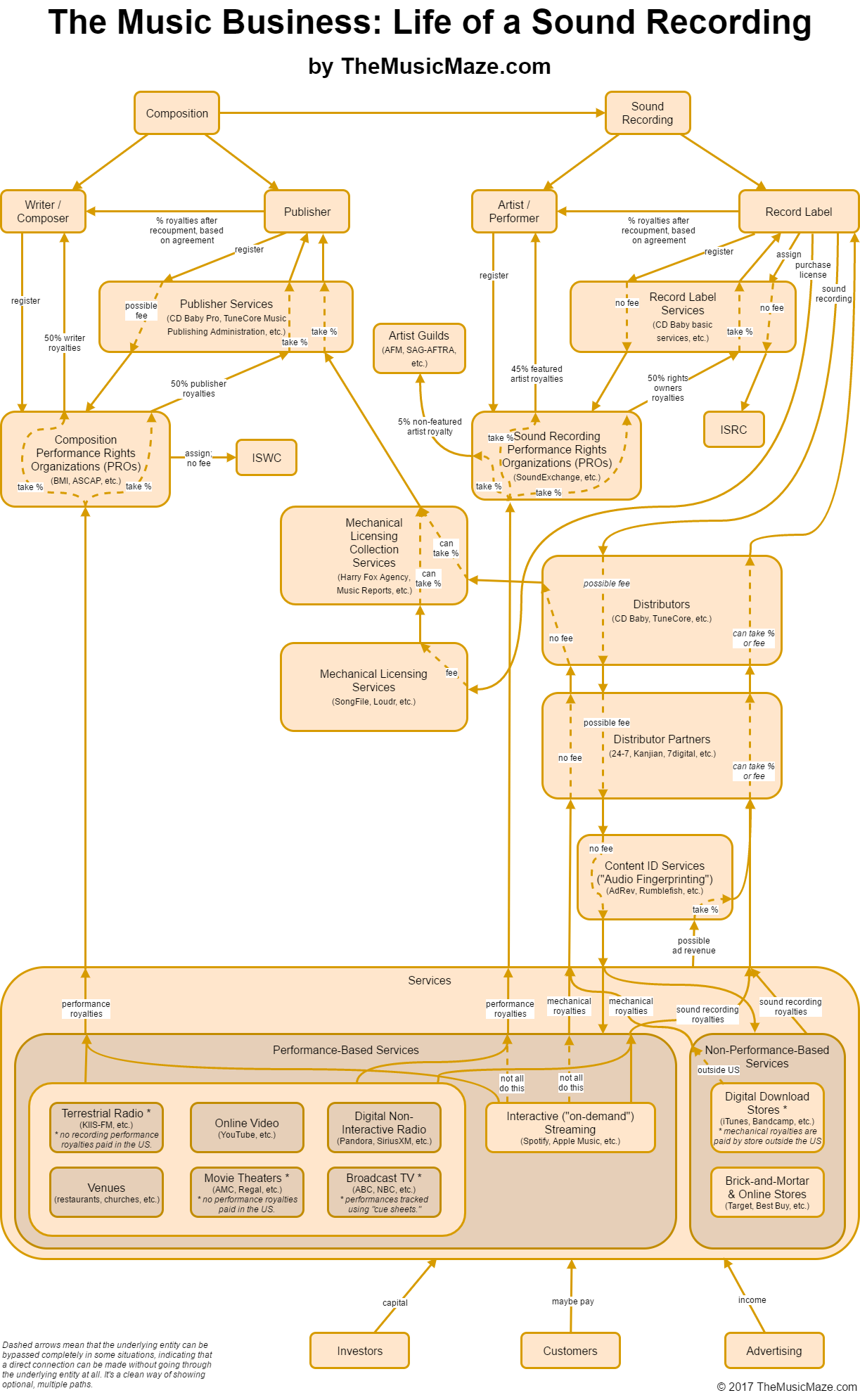

Show me the end-all music flowchart that I’ve been waiting for!

Where does that leave us? Well... we’re done (at least for what I want to cover in this article).

This is pretty exciting... without further ado... here is the final diagram (basically the same diagram as last one above, but all in the same color and with a nice title). I call it “The Music Business: Life of a Sound Recording.”

Finally, I leave you with this.

There’s no way that I can cover everything in that diagram in this post... but that’s why I created The Music Maze: you’ll find lots of different articles that go into detail.

Now that we’ve covered the basics of the major parts of the music business, I thought it would be fun to include a little table that shows you some more examples of the symmetry between the composition and the sound recording.

| Composition | vs | Sound Recording |

|---|---|---|

| Writer / Composer | vs | Artist / Performer |

| Publisher | vs | Record Label |

| Performing Arts (PA) Copyright | vs | Sound Recording (SR) Copyright |

| PRO (BMI, ASCAP, etc.) | vs | PRO (SoundExchange, etc.) |

| ISWC | vs | ISRC |

| Physical Songbook | vs | Physical CD |

| Digital Sheet Music | vs | MP3 |

| CD Baby Pro | vs | CD Baby |

| TuneCore Music Publishing Administration | vs | TuneCore |

| Sync License | vs | Master Use License |

| Prince writing "Nothing Compares 2 U" | vs | Sinead O'Connor performing "Nothing Compares 2 U" |

About The Author

Isaac Shepard is a full-time independent musician, pianist, and composer. He is also the owner of Shepard Audio, an indie record label and publisher. His music reached #1 on several iTunes charts in the US and in many other countries, and has been streamed hundreds of millions of times worldwide on music services such as Pandora, Apple Music, Spotify, and YouTube. He has published dozens of albums and has written music across many genres for TV, commercials, short films, web videos, and for over 15 video games. Isaac lives in Orange County, California. With three decades of music experience, he created TheMusicMaze.com to give other independent musicians a jump start and to help them better understand how the music industry works.