Interviewed by Michael Laskow

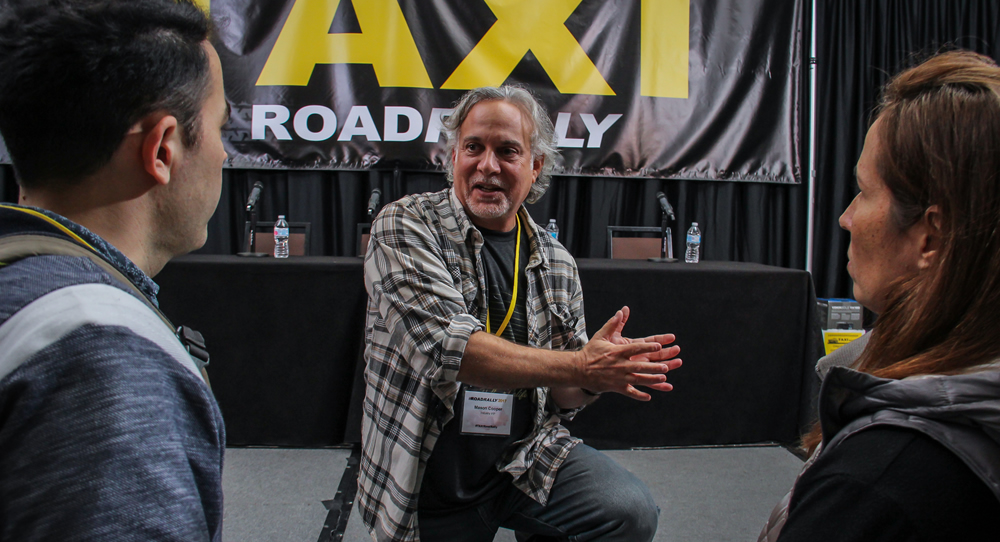

Music Supervisor Mason Cooper went above and beyond after the panel, when he hung out for about an hour meeting members, answering their questions, and checking out some of their music as well!

Panelists: Music Supervisors Mason Cooper and Frank Palazzolo

Moderator: Michael Laskow

Audience Member: Hello, my name is Isabella Rivera and I’m a singer/songwriter. I am in an agreement for one song with a studio owner who is also a musician. For this one song, he wants me to split copyright 50/50 with him, and then pay him for studio time. But he also said that he would have nothing to do with the rights or what happens to it... Not the rights, but what happens to it; that would be my decision. So would that be considered one-stop?

Mason: Let me get this straight. You wrote a song, you’re the artist, you went to a producer and he produced the track, right?

Audience Member: He helped me with the chords, yes.

Mason: Did you pay him?

Audience Member: Yes, I’m paying him. But he is the studio owner, so I’m paying him his hourly fee for the studio.

Mason: OK, now you’re really getting my ire up, because I just cannot stand when somebody says, “I want to...” Does he want to be a writer or a publisher?

Audience Member: He wants to be co-writer.

Mason: Because he wrote the chords? I would say this: It’s kind of like when a musician says, “Well, I want to be a writer, because I created that cool bass loop,” right? But if Celine Dion records it, or Toby Keith records it, and they’re not using the bass loop, are you still a writer on that? So that comes to this old question of who wrote the song. I have a big issue with people saying, “Well, you didn’t know how to play, so I created the chords.” But tell you what: 99% of the time, the chords are gonna be pretty darn obvious, even if you use an alt-minor, the A-minor instead of a C, blah, blah, blah, they’re going to be pretty obvious.

When someone asks to be a writer on your song, I have even a bigger problem than if they just want to own publishing, which is the business of a song. It’s kind of like when someone says, “I like your baby; can I be the birth parent?” [laughter] It’s like, “No.” Now, if they said they want to adopt my baby, that’s legitimate discussion maybe, but can they be the birth parent? No! I have an ethical issue with that, because you paid them.

Now, sometimes they’ll get publishing, so I would go back and say, “I’ll give you some of the business of the song.” Unless you feel that what they did creatively—maybe when they created the chords and the melody, therefore, maybe changed—there is a legitimate discussion for that. I’m not badmouthing the person; I don’t know the situation.

But, back to your one-stop question. If that person wants rights, but will assign to you the right to license on that person’s behalf, that’s a one-stop. As long as you can license for 100% of the song and the recording, that’s a one-stop.

"When you pay a producer, you’ve paid them, so they got their money. It’s kind of like when you pay somebody to sing on a song, they got their money, they don’t own the master because you paid them to sing on the master."-Frank Palazzolo

Frank: Real quick—when you pay a producer, you’ve paid them, so they got their money. It’s kind of like when you pay somebody to sing on a song, they got their money, they don’t own the master because you paid them to sing on the master. Now if you paid somebody to help create a song, and then they want to be paid and also own part of the song, they technically own more of that song than you do. Because you’ve now invested your money into the song, and you’re giving them an equal split on that. That’s not really a fair deal in my world. It’s like, wait a minute, so I gave you a $1,000, and you own as much of the song as I do? It should be, “I paid you $1,000, which takes you off of the master, and if you feel like you contributed to writing, then sure, you get 20% of the publishing as well. But to be a 50/50 split after you’ve already paid them to do their job—which is a producer’s job, which isn’t just to sit at a computer; it’s to help you create the song properly.

Mason: Right, they’re producing, they’re not an engineer. They’re not a button-pusher.

How do you draw the line between coming up with the chord progression and deciding the drum beat?

Frank: I don’t know. If you came in and you already had the song and you had it laid out, you had the skeleton of the song laid out from top to bottom and then they turn in into a song, that’s producing the song.

Mason: I say come up here with your guitar and sing me the song.

Frank: Anyway, just be careful when you’re paying for things and also sharing your song.

Mason: But that also brings up another point. When you have a session, get session forms and studio forms that basically say, “I paid you to play guitar. You’re not a writer. You don’t own anything. It’s a work-for-hire. I paid you. Thank you, goodbye.” Same thing with a singer, because you don’t want them coming out going, “Wait, I should get...”

"Our ass is on the line when we bring your song to our director or our producer or to the showrunner."-Mason Cooper

Another interesting fact, but I’m not an expert on this. I recently learned—I believe I learned this from Michael Eames while interviewing him on an episode of TAXI TV—do you know that in a situation like that, if this young lady (from the audience) goes to a studio, pays a work-for-hire fee to the producer or doesn’t get a signed agreement, and that person technically owns the master.

Let me change this. I do a song with Frank. He engineers and produces it, we co-write it and he says, “But I own the master. You’re using my studio and my chops to lay this down,” and now he owns the master. Ultimately, Frank will make a ton more money on YouTube plays as the master owner than the songwriters make as a result of owning the publishing. I didn’t realize that, but apparently it’s a huge ratio in favor of the master owner versus the copyright holders.

Mason: A little bit aside from that, but there is a thing of, you know, he who pays owns. So if you pay, you own it. It is good to have a piece of paper just to say, “I did pay you; you did receive this money; you don’t own it.” Or if they say, “Well, normally $5,000, you paid me $1,000, then I’ll pay you the $1,000 and we own X percent.” So have a paper trail. Protect yourself. It’s uncomfortable to do at that time, but it’s gonna be really more uncomfortable when the song is successful.

Frank Palazzolo (right) is a passionate Music Supervisor who loves to share what he’s learned during his career. In this shot, he’s chatting with Charles and Julia Brotman from the Hawaii Songwriters Festival!

Now, here’s a question that I’ve had to deal with—with Cassidy (Mason’s daughter who is a singer/songwriter), actually. She would, as the singer, write with a co-writer, and the co-writer owns the studio— because nowadays people own studios—and they would do the demo and the demo master and all that, and there would be a question of who owns the master. So I came up with this very easy answer on their behalf. Well, you did the track, but she sang. You didn’t hire her as a singer, she didn’t pay, so you co-own the master because she performed, and you performed. Now, if sometimes that person said, “What if I take this track? We both co-wrote the song—I’m not arguing that—but if I wrote the track and I get another (different) singer on it, then you own that master.” But the one that she sang on you co-own, because you pay her, you can buy her out. So these are conversations to have, just communicate with your people.

"You want $7k, we say we only have $6k. We’re not saying ‘no’ to the $7k because that extra thousand bucks goes in our pocket."-Mason Cooper

Audience Member: First, thank you and Michael, and everybody who puts this event on, because this is really fantastic. But what came up a few questions ago was something that Mason brought up, a very important element, and that is there might be new people who are writing material who don’t have that IMDB database yet, they are not in there, they don’t have the creds yet. And you said, “All I’ve got is 13 cents for the budget for this song.” What a lot of people might have heard in that was the negativity. What I’d like you to maybe speak to is what are the benefits of that?

Mason: That’s a great question. I have limited budgets, I think more limited budgets than a lot of your shows (as he points to Frank). I use a lot of music. If you look at my IMDB, I’ve got a ton of projects always going, so that can help make it up in quantity. When you’re in the business of getting your song used, it’s not exclusive, you’re not giving up ownership. If your song is used in a bar scene that you can hardly hear—because the source thing playing (like it’s coming from a jukebox) and it’s kind of groovin’ through, but it’s in there—that’s not going to stop [Frank] from using your song either. A use is a use, is a use. Now, maybe if it’s featured, if it’s an end-title feature thing, that might stop someone: “Well, that was a theme song (meaning that it’s more obvious or ‘visible’ to the public); so I can’t use it.” But for most of the uses that you’re gonna have, if you can make any upfront money, great. But if I’m doing a film for a film festival, there are no royalties for that unless it ends up on TV. But, if it’s a TV show, you’re gonna get your ASCAP/BMI/SESAC royalties, so you are going to make back-end money.

But also, nobody else knows the deal you made—that’s your private business. I find it rude for someone to say, “Hey, you’re working as an accountant? How much did you make this year?” Nobody should know your personal business. So all they know is you got a song used. Nobody in our business is going to say, “Well, how much did you license that for, because I’m gonna lower my fee if I [find] out [you licensed it last time for very little money]?” Nobody knows. Nobody’s going to ask you how much you made on that. So all of a sudden your track record goes up [even if you’re not getting a big sync fee]. Your track record goes up, which let’s us know that, oh, a lot of people are liking your music. And you also have licensed it to those shows, so now you’re not a newbie where we have to explain what the clearance is; we don’t have to educate you just to use your song. You’ve had five or six uses, you’re educated. Love your song; love to license it.

So the benefits are, you get a use, you build your resume, you make money, you make royalties, you build your credibility. It just builds up, and you learn the process. You understand things, and it should feel darn good that you forget what the money is... Because here’s the deal—our budgets are our budgets. That’s why I say don’t be offended. We wish we had extra zeros on the end of all these clearance quotes. We liked your song; we want to use your song. Our ass is on the line when we bring your song to our director or our producer or to the showrunner. So when we bring your song to them and they like it, doesn’t that feel good to you that now you got a song used in there and it made it through the system (meaning all the various people who have to approve it) and they still liked it and it’s in the show; [you’re] actually on the path to doing something. Thank you for that question.

"If I come up under budget, they don’t give me money. They take my money, and they say, 'Thank you very much for coming in under budget.'"-Frank Palazzolo

Frank: Yeah, it was a great question. Think about how much money you’re making with music as well. I’ve got people who have never had a sync before, and they’re telling me that we’re not paying enough money for a $4k sync or a $6k sync. I’m just like, “You have never had your song licensed before; $6k is a really, really nice fee for the type of use that this is.

Mason: That’s a really good fee!

Frank: That’s a great fee; how can you argue with it?” And they’re like, “OK, great, maybe we can do it for $7k.” You’re negotiating. This is when you get yourself into the danger zone, because we will quickly be like, “You know what? Screw it, you’re done.”

Mason: Guess what, you want $7k, we say we only have $6k. We’re not saying no to the $7k because that extra thousand bucks goes in our pocket.

Frank: We don’t get anything.

Mason: We don’t have it.

Frank: And here’s something to keep in mind also – and this is pretty funny – I’m employed by networks to get good music, but if I come up under budget, they don’t give me money. They take my money, and they say, “Thank you very much for coming in under budget. We’re now going to give your money over to craft services and to graphics, and you’re gonna get less money next season, because we know you can do it under budget.” I promise you, I want to spend the money.

Mason: We’re not low-balling you.

But if you show up on set, you get extra food.

Frank: Yeah, you get a filet mignon,

Mason: Twizzlers, Skittles.

Frank: So if we come in low, it’s not because we don’t want to pay you, it’s because we can’t pay you. If it’s a main end montage, yes, $250 might be a little low. But if the episodic budget (meaning the entire music budget per episode) is $5,000, you might be kind of where you’re supposed to be. Just saying measure where it is, measure what the show is.

Mason: Guess what. I have my budgets, I have what I call my “friends and family”—literally my friends and family—and I will sometimes put their songs in my shows for gratis, for zero, because I need to make my budget switch. And they look at me and go, “Dude, BMI and ASCAP.” I get calls from people like that every three months. “I just got mailbox money—thanks.” Because I had no budget, I went, “You know, your song, I can’t even hear that it’s playing. I’m gonna use your song and I don’t have to spend a dime.” Friends and family. So they’re willing to take zero. I’m not going to ask you for zero ... usually.

You guys are amazing, and thank you so much for hanging out and doing this extra hour. Mason Cooper and Frank Palazzolo, ladies and gentlemen! [applause]